A general understanding of the lumbar disc is needed in order to get a good grasp of the annular fissure. Particularly what the disc is made of and how it functions.

After covering the anatomy and function of the disc the annular fissure is broken down. Types of annular fissures and possible causes are outlined in depth.

Perhaps more importantly the prevalence of annular fissures in symptomatic and asymptomatic populations is explored. The association between pain and annular fissures is also highlighted.

Lumbar Disc Anatomy 101

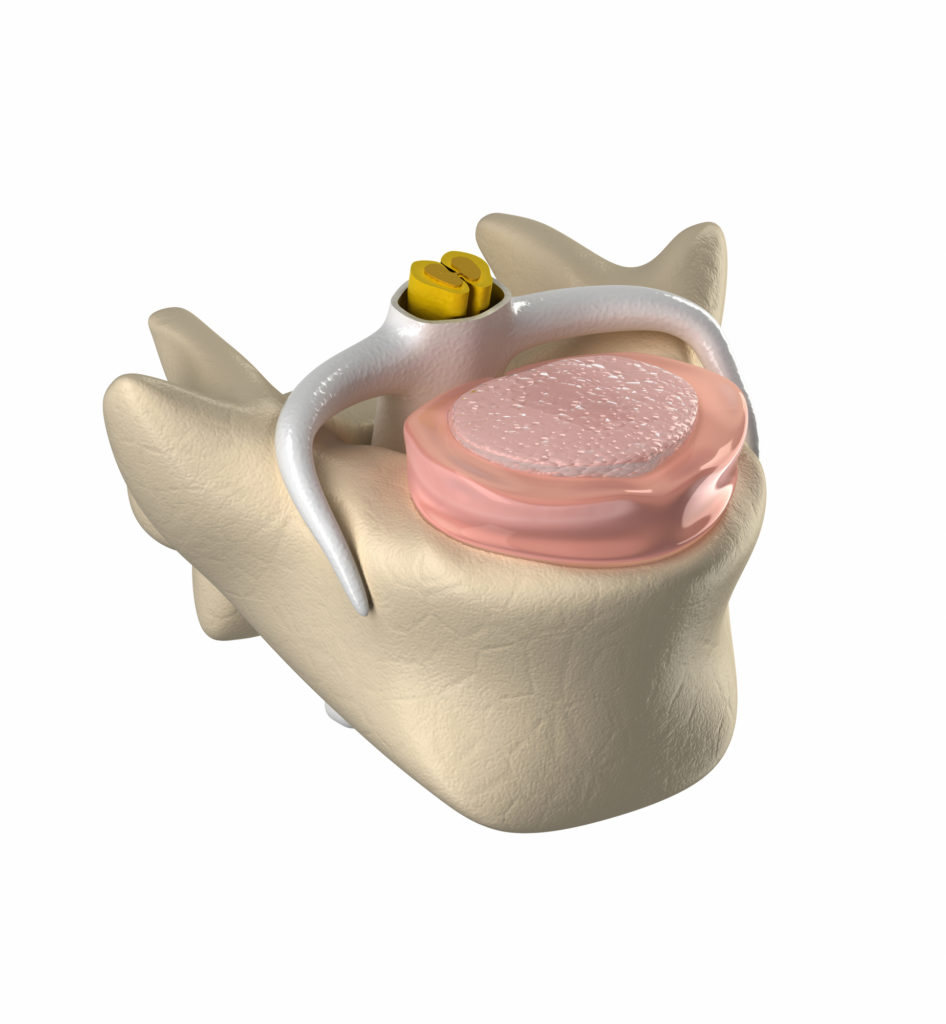

The discs between the vertebrae are comprised of two parts. The annulus fibrosus and the nucleus pulposus.

The outer pink part is the annulus fibrosus. The inner pinkish part that is held in by the annulus in the nucleus pulposus.

The annulus fibrosus forms the outer layer of the disc and is made up of 15 to 25 stacked layers of collagen. Each layer is oriented 60 degrees from the layer adjacent to it. This orientation increases the strength of the disc while allowing flexibility.

The annulus functions as a strong, rigid container to hold the nucleus pulposus in place. In addition to keeping the nucleus contained the annulus fibrosus also stabilizes the spine by resisting torsion, flexion, and extension.

The nucleus pulposus is a gel-like structure in the middle of the disc. It’s made of up water, collagen, and proteoglycans. 66% to 86% of the nucleus is water.

Lumbar Disc Function

The nucleus functions to spread forces out over the vertebrae above and below it, preventing excessive forces through one part of the vertebrae.

Consequently the lumbar spine can move through considerable ranges and tolerate countless activities without compromising the vertebral bodies.

The disc acts as a force distributor, link, and cushion between vertebral bones. It allows motion while also stabilizing the spine and resisting excessive movement in any one direction.

So…What is an annual fissure?

An annual fissure is simply a deficiency of one or more layers of the annulus fibrosus (1).

The term annular fissure is preferred over annular tear, although the terms are synonymous. Fissure is the more appropriate term because “tear” infers an injury. Annular fissures are generally not due to injury, occurring slowly over time.

The posterolateral (back and side) portion of the annulus fibrosus has collagen fibers that are oriented in a more vertical direction, making this region weaker and more susceptible to fissures. Consequently the posterolateral annulus is where the majority of annular fissures occur.

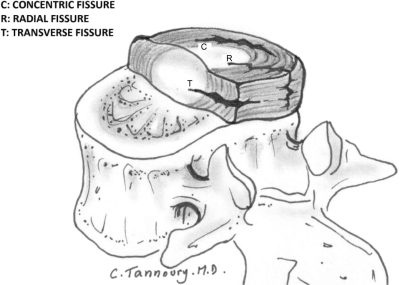

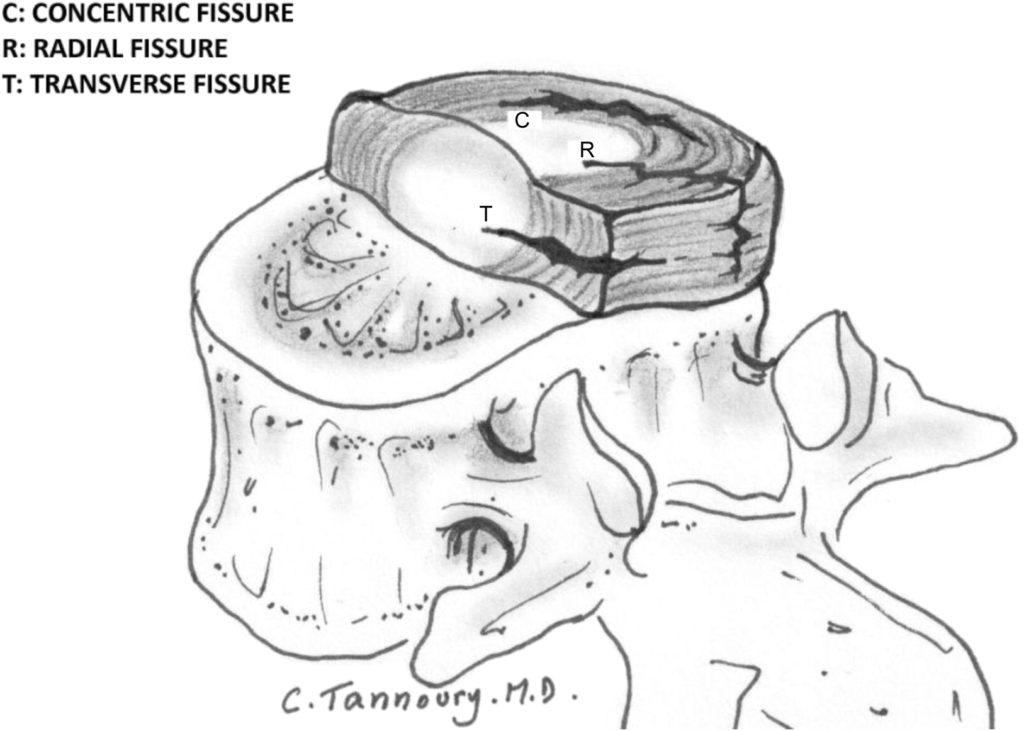

Annular Fissure Types

- concentric

- radial

- transverse

Concentric fissures involve separation of annular fibers parallel to the outer part of the disc. They are commonly found along the posterolateral part of the disc.

Radial annular fissures are the most common type and are simply are part of aging. Radial fissures are found regularly in people WITHOUT lower back pain. They start on the inside, where the collagen fibers of the annulus fibrosus blend with the inner nucleus pulposus. Radial tears work their way from the inside out, towards the periphery of the disc.

A transverse fissure starts along the part of the disc that attaches to the vertebral body. Transverse fissures usually start on the outside and work their way in, towards the nucleus pulposus.

Radial annular fissures go hand in hand with disc herniations. For the disc to herniate there must be a compromise of the annulus. The nucleus pulposus must have a place to push out through. If the annulus is completely intact there is nowhere for the disc to herniate.

So, if there is a disc herniation there is an annular fissure, by default.

How common are annular fissures?

A 2004 study of cadaver lumbar spine discs show that annular tears are more common than once believed and that they begin early in life.

In this particular study annular tears were found in 60-70% of young adults, aged 30-34. By age 65 annular fissures were basically unavoidable (2).

More than half of people aged 20-34 showed evidence of annular fissures (2).

19% of 20-year-olds WITHOUT back pain have annular fissures. 29% of 80-year-olds WITHOUT back pain have annular fissures (3).

An Annular Fissure Doesn’t Always Mean There’s a Problem

A recent study in the European Spine Journal shows that having an annular tear does not lead to faster or greater disc degeneration. The study looked at 450 discs in 90 patients over a four year period. One quarter of the discs with an annular tear showed progressive degeneration over a four year period. One quarter of the discs WITHOUT an annular tear also showed progressive degeneration over the four year period. So annular tears were not associated with increased disc degeneration in this study (4).

“Abnormalities” are normal in the middle age spine. According to research published in the journal Spine in 2005 25-50% of 40-year-olds have annular tears, disc protrusions, facet joint degeneration, endplate irregularities, or foraminal stenosis (5).

A 2013 South Korean study showed that a stunning 76.1% of people WITHOUT lower back pain had an annular fissure (6). This number is high compared to other nations. The authors state the high incidence of disc herniation and annular fissure could be due to three variables. First, they used a high-resolution 3 Tesla MRI, which might simply do a better job of capturing the images. Second, many of the subjects had a background in agricultural work. Third, the people in Korea sit cross legged on the floor frequently and for long periods. This results in prolonged spinal flexion at or close to end-range, would could contribute to the herniations and annular fissures.

Even so, NONE of these people had lower back pain. Even with these findings on MRI.

At study that looked at the association between MRI findings and low back pain concluded:

“Though some patients and spine care providers regard the presence of annular tears, disc bulges, and disc protrusions as ominous, these abnormalities did not appear to predict new-onset back or leg pain in this study”, according to Deyo (7).

So basically the take home point is this; annular fissures are a normal finding in people who have NO back pain or history of back pain.

Can they cause pain? Yes.

Can they be part of the picture if you have lower back pain? Yes.

Just be well aware that they are basically normal and nothing to get too worked up about.

Do annular fissures cause pain?

Most annular fissures likely don’t cause pain, based on the medical research literature showing how common they are in people without lower back pain.

That said, annular fissures that extend all the way through the annulus fibrosus are associated with pain. The risk of frequent back pain is 42% for people with “leaking tears” or tears that extend through the entire annulus fibrosus. The risk of frequent lower back pain is only 20% for incomplete annular tears and only 10% for those with an inner tear or no tear (2).

What to do if you feel like your lower back pain is related to an annular fissure

Since radial annular fissures are the most common type and are always present with disc herniations it’s best to treat annular fissures with the same types of exercises as a disc herniation.

Exercises, positioning, and movement work that decreases disc related pain almost always reduces symptoms related to annular fissures.

After all, an annular fissure occurs in the disc and is present with disc herniations, by default.

Powerful Bulging Disc Exercises that Destroy Pain outlines three simple, effective exercises you can start today. These three exercises are a great place to start if you feel an annular fissure or disc bulge is causing your lower back pain.

Proven Herniated Disc Exercises outlines why exercise is beneficial and how it promotes the healing process while decreasing pain. A number of specific exercises are outlined, as well as exercises to avoid when you have a herniated disc. The overreaching principles that can be used to turn any exercise into a disc healthy activity are explained.

Use these two articles to start working on exercises that have been proven to reduce disc related lower back pain.

FAQs

An annular fissure is a deficiency of one or more layers of the annulus fibrosus, the outer covering of the disc. The term annular fissure is synonymous with annular tear. Annular fissure is preferred over annular tear because tear infers an injury. Most annular fissures are not due to any one injury, but occur slowly over time. As part of the natural aging process. Annular fissures are common, occurring in people with and without back pain.

There are three types of annual fissure. Radial, concentric, and transverse fissures. Radial annular fissures are the most common type and go hand in hand with disc herniations. Radial annular fissures are also found regularly in people without lower back pain and are considered a normal part of the aging process.

An annular fissure in the lumbar spine is a deficiency of one or more layers of the annulus fibrosus (outer covering the lumbar disc). The disc has an inner part, called the nucleus pulposus. The outer part, the annulus fibrosus bascially contains the inner part (nucleus pulposus). An annual fissure occurs when the outer part pulls apart. This generally happens along the back and side part of the disc, where the collagen fibers are oriented more vertically. The vertical orientation makes them more likely to fissure. Radial annular fissures are the most common type. Annular fissures are not necessarily pathologic, they are considered a normal part of disc aging and are found in people without lower back pain.

Medical research shows that annual fissures are common and a normal finding in people without lower back pain. Although some types of annual fissures are more likely to be associated with pain, particularly fissures that extend all the way through the annulus fibrosus. Because annular fissures are present with disc herniations it’s best to address annular fissures in the same manner as a disc herniation. Disc related lower back pain usually decreases substantially within the first six weeks of onset, though may still be present after this time. Disc healing times vary widely, from five to twenty-two months. This time frame can be applied to annular fissures as well. Although the fissure may not heal completely. It’s important to focus on movement patterns and exercises that minimize tensile, torsional, and compressive loading through the disc while strengthening the trunk muscles.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459235/

- Videman T and Nurminen M, The occurrence of annular tears and their relation to lifetime back pain history: A cadaveric study using barium sulfate discography, Spine, 2004; 29:2668–76.

- Brinjikji W, et al., Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations, American Journal of Neuroradiology, 2014, prepub ahead of print; www.ajnr.org/content/early/2014/11/27/ajnr.A4173.long

- Farshar-Amacker NA et al, European Spine Journal, 2014; 23:1825-9. Doi:10.1007/s00586-014-3260-8.

- Kjaer P et al., Magnetic resonance imaging and low back pain in adults: A diagnostic imaging study of 40-year-old men and women, Spine, 2005; 30:1173–80.

- Kim SJ, et al., Prevalence of disc degeneration in asymptomatic Korean subjects. Part 1: Lumbar spine, Journal of the Korean Neurosurgery Society, 2013; 53(2):31–8.

- Suri, Pradeep et al. “Longitudinal associations between incident lumbar spine MRI findings and chronic low back pain or radicular symptoms: retrospective analysis of data from the longitudinal assessment of imaging and disability of the back (LAIDBACK).” BMC musculoskeletal disorders vol. 15 152. 13 May. 2014, doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-152

- Fardon DF, Williams AL, Dohring EJ, Murtagh FR, Gabriel Rothman SL, Sze GK. Lumbar disc nomenclature: version 2.0: Recommendations of the combined task forces of the North American Spine Society, the American Society of Spine Radiology and the American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine J. 2014 Nov 1;14(11):2525-45. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.04.022. Epub 2014 Apr 24. Review. PubMed PMID: 24768732.